I recently had a chance to hear Dr. Karl Kruszelnicki on triple j radio in Australia. Known simply as Dr. Karl, he has a weekly national show answering science questions on an alternative rock radio station. Yes, science on rock radio. Yes, national. Yes, Thursday morning – when people are listening. Frankly, he is good -- really good, really interesting with a continuous number of callers wanting answers to science questions.

This got me thinking, what can we learn from the top popular science communicators of our time? So I spent some time listening and reading some of their past work to determine what I could take away. Make no mistake about it. Learning to communicate technical information is a work in progress for all of us. Learning from these masters can help. Starting with Dr. Karl.

Dr. Karl

Dr. Karl covers a remarkable range of facts and background materials. One of his common methods of relaying information is a form of storytelling. Specifically, the stories are importantly related back to the listener’s personal experiences. Psychology researchers Schank and Abelson have a term for this: they call it “mapping the speaker’s stories onto the listener’s stories.” Consider the following examples from a recent show.

A listener was wondering why ice evaporates if left for a long period in a freezer. Dr. Karl responds with, “Think about water on a little puddle in the road. It does not get above 100 degrees C but it evaporates…”, the reason is explained that some of the molecules in the puddle do get to 100 degrees. He goes on to explain that something similar happens in the freezer, but at a much slower rate.

Of interest is how he explained this. Clearly, it was easier to “map” this story onto the image of a puddle on the road, as opposed to what the conditions are inside a freezer.

Another listener had a question about GMO crops. To give a background he starts with an image for the listener. “Have you ever been walking along a long a field of long grass, and you see those little tiny grass seeds that are about the size or smaller than the size of a match? That’s corn.” He goes on to discuss how grass seeds were bred into corn over thousands of years. Again, mapping to a familiar image of walking in a field. Then after that background, he discusses the modern approach to producing GMO crops.

The Dr. Karl weekly shows are available as podcasts. There is a lot to learn from him, both science and the art of presenting information. Additionally, during winter in the Northern hemisphere you can almost hear the sunshine through the broadcast from downunder.

Carl Sagan

With his Cosmos series Carl Sagan became an icon for science communication. One unquestioned takeaway from his work – enthusiasm and passion. Additionally, his use of easy to process terms. For example, “We are made of star-stuff.” By star-stuff he was meaning the heavier elements created in stars. We constantly hear the advice to avoid using jargon, but we are never told what to do. The brothers Dan and Chip Heath in their book “Made to Stick” recommend we should work for “universal language”. Star-stuff is a perfect example of universal language. Star-stuff “sticks” with an audience better than heavy metals. His “star stuff” phrase and his “billions and billions” phrase from Cosmos became catch phrases because they worked and the passion demonstrated when he used them.

Later in his famous Pale Blue Dot speech referring to a distant image of Earth taken from the Voyager 1 spacecraft, Sagan speaks with the same unbounded passion, even bordering on sentimentality.

“From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it's different. Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

Truly Sagan was passionate about his topic.

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson has in many respects assumed the role of Sagan including a remake of Cosmos. His approach is also passionate bordering on emotional. In Cosmos he reflected on what science means to him in a very personal way. He talks about the wonders of the universe by telling stories through the challenges and discoveries of his predecessors – very human stories.

Bill Nye

In my mind I have a hard time separating Bill Nye from Mr. Rogers. Both are associated with public television in the United States and both taught children with a comforting approach. Known as “Bill Nye, the science guy”, his work has now covered many areas, but the lesson from his success to us is clear – comfort with the messenger.

Sir Arthur Eddington

These current communicators are channeling the example set by one of their predecessors. It is a name we do not hear much about today, but in his time Sir Arthur Eddington was a famous popular communicator. Eddington was an English astronomer and physicist in the early 1900’s. He was known for the first explanations of Einstein’s theory of relativity in English and is credited with first confirming Einstein’s theory that gravity will bend light. But he was most commonly known as a lecturer credited with persuading multitudes of people that they can understand relativity. Explaining relativity is unquestionably a difficult explanatory task. A brief excerpt from one of those lectures delivered at Cornell University and later published in New Pathways in Science reveals a familiar topic – storytelling.

“One of our first tasks must be to try to understand the relation between the familiar story and the scientific story of what is happening around us.” … “Physical science now deliberately aims at presenting a new version of the story of our experience …”

He recognizes that mapping his (in this case the theory of relativity) stories to the listener’s stories is difficult. His relativity stories seem to conflict with everyday observations. Understanding and dealing with those conflicts is the issue he recognizes he must overcome.

Lessons Learned

What are the lessons learned from these masters? Communication, including highly technical communication, is personal both from the perspective of the audience and the communicator.

Even at the high level required in the case of Sir Eddington, sharing some of the most profound discoveries of mankind, it is personal. We should relate to people and their stories and share ourselves. These masters do not hesitate to share themselves. They do not hesitate to share their personalities. Whether it be the lighthearted approach used by Dr. Karl and Bill Nye or Carl Sagan's sentimental soul revealing expression -- the message is personal.

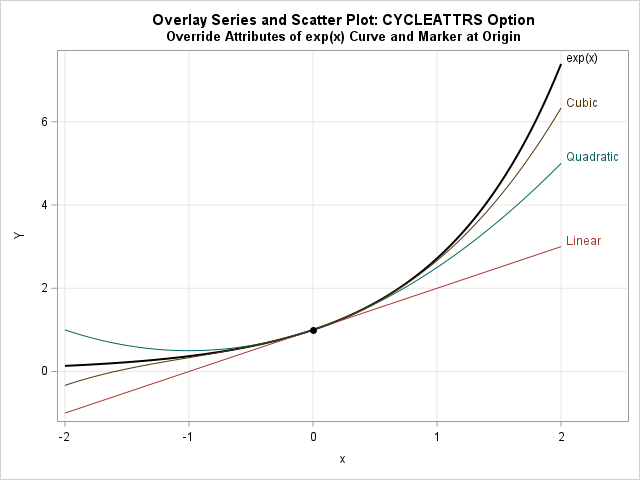

We too can make it personal. Analytics is an art form. Taking complexity and noise and producing a message is a powerful accomplishment. It can become part of you and can be shared as such – with passion.

You can learn more of these skills in my Business Knowledge Series course, Explaining Analytics to Decision Makers: Insights to Action.

3 Comments

what an interesting blog post. .and one after my own heart. as a technical trainer, I am constantly trying to relate technical sas topics to real life.. and now after reading your post I want to go check out each of these skilled scientists to learn more & share more... thanks for a great write

Dr Karl is an entertaining encyclopaedia. I love listening to his stories and wealth of information. Humanising the message, making it personal, certainly helps with communication. Your BKS course is a good way to attain these communication skills for the analytics knowledge worker.

Thanks for your comments.