One of Warren Buffett’s most famous quotes goes like this:

“Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

That time is now for interest rate risk managers, who have been basking in the warm sea of declining interest rates for most of the last four decades. At high tide.

Thanks to the sharp spike in interest rates, the two basis point yield on one-month Treasury bills of February 23, 2022 is a rapidly fading memory. No talking points or PowerPoint presentations can paper over serious interest rate risk management mistakes. This is an era of serious job insecurity for interest rate risk managers, most of whom don’t know much about 1982, Paul Volcker, the savings and loan crisis, and the hundreds of savings and loans and banks that failed over the course of the 1980s and 1990s.

Even before the latest bank failures hit the news, my recent conversations with interest rate risk managers at large banks worldwide revealed danger signs everywhere. The “tide table” for interest rate risk managers has these flashing red warning signs:

-

“We use interest rate futures to hedge generally accepted accounting principles to net interest income 12 months forward.”

-

“We’ve been using the same interest rate risk vendor for 20 years.”

-

“We use a one-factor yield curve model. The vendor tells us that’s all we need to manage risk well.”

-

“We don’t use default probabilities in our interest rate risk analysis. That’s done by the credit group.”

-

“We do interest rate risk once a month without fail.”

-

“We get our forecast for non-maturity deposits from the retail banking team.”

-

“Our analysis shows that the ‘surge deposits’ from the pandemic are here to stay.”

-

“Our bank benefits when there’s a banking crisis. The depositors of the bad banks come to us, and that experience is built into our risk analysis.”

These quotes are all real, and they terrify me. It seems like 1982 all over again. Many of the most analytical people in the interest rate risk arena have moved to other disciplines in banking or left for unregulated financial services firms. I got my first banking job in risk management at Security Pacific Bank when the interest rate risk tide went out on my predecessors in that function. They just disappeared suddenly, and no one ever told me their names. By 1982, after the interest rate function had been rebuilt, the asset and liability management committee at Security Pacific Corporation included four people who would ultimately serve as bank CEOs and four PhD holders in a group of 12. By contrast, the 30-member interest rate risk group I attend regularly has no members with a PhD degree. I suspect that will change soon.

Learn more about asset & liability management – and the benefits of a holistic approach to risk.

Assessing risk of a one-factor model

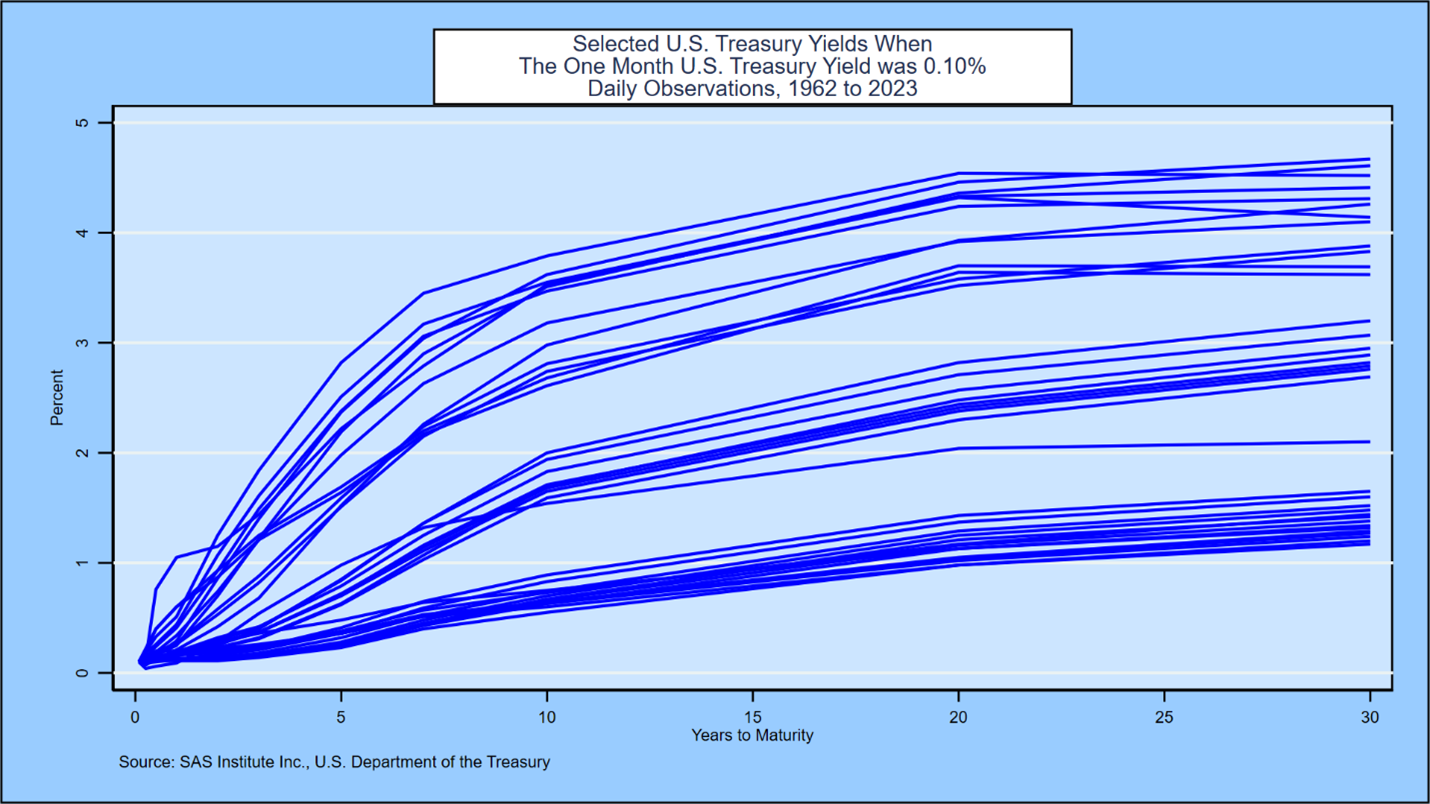

Of the comments above, the one that scares me the most is the quote about a one-factor interest rate risk framework. There’s a simple experiment to assess the risk of a one-factor model. Take the history of the one-month Treasury bill, which is the shortest maturity Treasury yield currently reported. Tabulate the rate levels to see what short rates have been experienced most often. The one-month Treasury bill has been two basis points on 306 trading days. It’s been 10 basis points on 79 trading days. At a 5.18% level, there are 56 observations. The most famous one-factor term structure model was published by my friend Oldrich Vasicek in 1977 when he was working at Wells Fargo Bank. Given the short rate of interest and two parameters, Vasicek was able to derive the entire yield curve (assuming the model is correct). Here’s a graph of most of the US Treasury yield curves that prevailed when the one-month Treasury bill rate was 10 basis points:

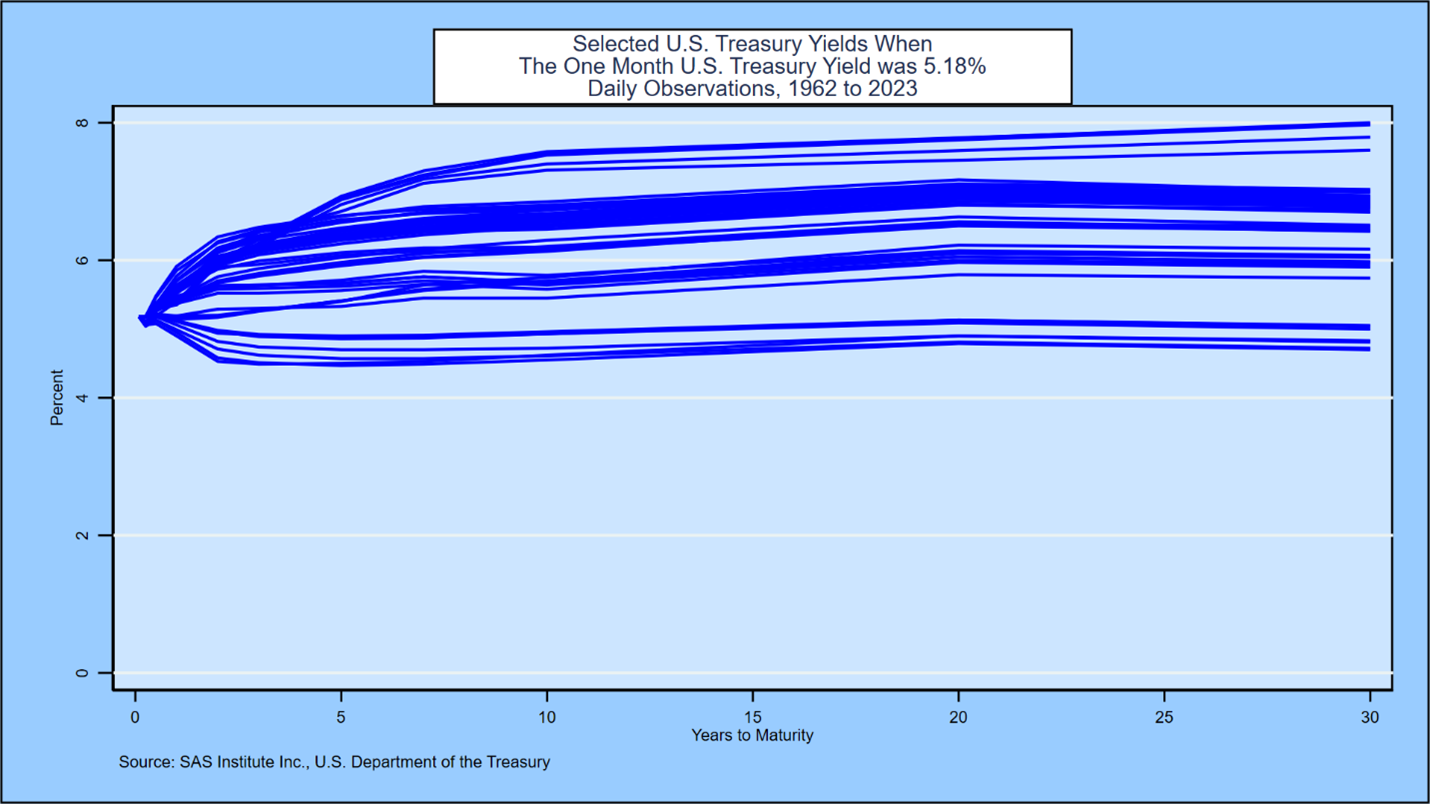

Here’s a similar picture of most of the Treasury yield curves that prevailed when the one-month Treasury bill was 5.18%:

In a way any bank CEO can understand, these graphs show that bankers relying on one-factor interest rate models are seriously at risk in the current environment. Valuations are wrong, capital adequacy calculations are wrong, hedges are wrong, and the correlation of rates, oil prices, and commercial real estate is completely ignored. The latter correlation has devastated the banking and savings and loan industries twice in the past, with a $1 trillion cost to US taxpayers each time.

Learn from SAS financial risk experts in this webinar on sound risk management processes for banks amidst the current crisis.

SAS is sharing this blog post in the spirit and promotion of thought leadership and to spark dialogue on current events. Thought leadership content does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation by SAS, and the views expressed by contributors are their own. If you have any questions about this disclaimer, please contact SAS for assistance.

2 Comments

That's a very thought provoking post. Thank you Donald for pointing out the warning signs which have been taken for granted without thorough validation.

Hope to speak to you in person some day

Thank you for the kind words. I'm looking forward to discussing this in person as well!