I brushed aside some sawdust on the workbench and set my laptop down. It wasn’t really mine. SAS Library Services had kindly lent me a new laptop for the “Making Sense of Sensor Data” workshop at UNC’s BEaM Makerspace. I had just set the laptop down…in sawdust. Like any normal person, I immediately began to think of a good lie I could tell when I returned the laptop.

SAS: Why does this laptop smell like sawdust?

ME: I don’t know. I noticed that, too. I think it must be Windows 10.

SAS: Windows 10?

ME: Yes, I think Windows 10 just smells like that.

SAS: But we don’t have Windows 10 on that laptop.

ME: No, of course not. It kept asking me if I wanted to install Windows 10 and I kept clicking “no” and then I smelled something like burnt leaves…

SAS: Windows 10?

ME: Yup. I think I read about this online somewhere. They call it the “Winter Woodburn” scented desktop.

That’s the problem with lying. There are a small group of people who are exceptionally good at it and the rest of us are lousy. I decided I would defend myself with the truth.

“Yes, I set the laptop down in some sawdust,” I would say, “but at least I didn’t set it down beside the table saw.” That would earn me some points back, I thought. Resolved, I pressed the power button to turn the laptop on and proceeded as planned. To my relief, the loaner laptop was apparently impervious to a little sawdust.

The sensor data workshop

UNC (Chapel Hill) is home to two makerspaces. One is in Kenan Science Library. That space is the kind of clean, well-lighted place you would expect in a library. The other, BEaM, is in the basement of Hanes Art Center. Follow the signs, down the stairs, around the corner. BEaM is a classic workshop: massive laser cutter, table saw, large heavy desks, and walls covered with hanging drills and other tools. Students don’t just make things there; students build things.

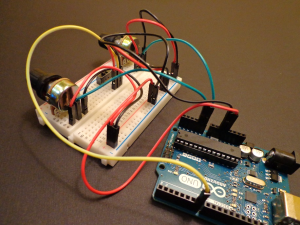

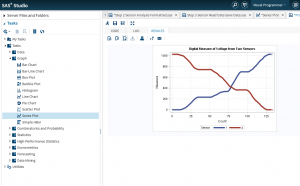

For our workshop, we were not going to use any of that heavy machinery. We were building Arduino circuits, gathering sensor data, and analyzing the results in SAS Studio using the no-cost online version of SAS for students. But having used a table saw, I could not help but wish we had made more elaborate plans like, say, mounting the Arduino to an eight foot long 2x4 and laser cutting a custom bracket for a laptop. Something big and dangerous. Maybe a catapult to send all of the data into a real cloud, a hybrid hosted Data Trébuchet (legal note: patent pending).

For the workshop, we were expecting about 12 students. More than 20 came. For two hours on a Tuesday night at BEaM, students and some faculty, too, sat elbow-to-elbow building circuits and analyzing data. The students were from a diverse set of majors ranging from computer science and biostatistics to international law and others. Some students knew each other and some made new friends.

We were all working like mad, building circuits, spinning potentiometers, pushing data into the cloud, and reviewing analytic output. Then, in a sudden quiet moment, I looked out across the room and wondered: Would anyone who has not stepped foot on a college campus in a decade know that this is what college looks like now? Is this what the average person imagines when they hear the phrase, “liberal arts education?” I doubt it.

What does a college education look like?

We are in the midst of a discussion about what college is supposed to be. In truth, this is a conversation we have been having for 100 years, rounding up from the 1916 publication of Dewey’s Democracy and Education. Given the rising burden of debt facing many college graduates and seismic changes in our economy brought about by The Digital Age, this a conversation worth continuing.

At the core is a simple question. What is the value proposition of a college education? These days, the question is more pointed. What is the value of a traditional bricks-and-mortar 4 or 5 year on-campus experience over, say, watching 1,023 videos online and answering 4,200 multiple-choice questions to verify that you were paying attention? If the traditional college experience is just sitting in a large lecture hall watching a human being click through his or her PowerPoint, why couldn’t we do that without the classroom and, it has been asked, why would we need more than one teacher to teach it just once? Couldn’t that be done just as well much cheaper?

The defense has been that a traditional college experience provides much more than just certification. A degree is more than just proof that you navigated your way through some curriculum or passed X number of college credit hours. College is and should be something more.

Defenders of the traditional college experience say that the most important thing, the thing they value most from their college years, is the friendships and social connections made during those college years. But friendly human beings make friends wherever they go, even at work, even long after college graduation. People well into their 30s, 40s, 50s, and beyond gather to drink a beer and watch a basketball game together. It happens all the time, or so I have been told.

Or maybe college is something more

Let’s be honest. The implied value proposition of a traditional college experience is based on the expectation that, given the gift of time in this place with other students, students will learn something not taught in any class, something perhaps not even related to their major.

Simply put, we are betting that, provided some time and tools, students might do something really cool and that cool thing may turn out to be something absolutely amazing. For example, create SAS. Or design an algorithm that can quickly search through a googol of html pages. Or start a little record company that could turn Hip Hop into a billion-dollar industry. Or any of the other brilliant ideas and inventions dreamed up by college students in dorm rooms while they weren’t necessarily doing their homework.

Unfortunately, spontaneous innovation cannot be planned. There is no syllabus for this experience, no credit hours offered and no grade. We may not even know that it is actually happening when it happens. Even the most metric-savvy institutional research office may not be able to document it.

All we can really do is create a context where this can happen. These days, creating that kind of ecosystem requires much more than just putting a couple of sofas in a dorm lounge or hosting a cookout in the quad. That’s why universities have invested in libraries where you can check out a pair of Google Glasses the same way you check out a copy of The Great Gatsby, student centers with high-tech communal study spaces, open access visualization labs with floor to ceiling computer screens, and, of course, makerspaces like BEaM.

The expectation is that, given some free time and access to this kind of technology, students will take advantage of all of this to go beyond the textbook or lecture and, perhaps, beyond anything their own professors might teach them. Our expectation is that they will because we know that bright, creative people are driven to seek out and find other bright, creative people. When they do, great things happen. That is what we are expecting or, at least, hoping will happen.

At the BEaM workshop, we were expecting about 12 students. We had more than 20. On Tuesday night in the basement of Hanes for two hours, sitting elbow-to-elbow, we had a workshop for no college credit, not even the promise of a paper “Certificate of Accomplishment.” There were 20 students with an interest in learning something different just because a friend or a professor had suggested to them that it might be interesting. They had heard about the Internet of Things and wanted to learn more about how they may play a role in designing the future.

The conversation about the value proposition of a traditional college experience is important. How are colleges going to create a 21st century workforce? What are liberal arts universities doing to ensure students will have the necessary tech skills to compete? Where will we find students with the brains, the talent, the creativity, and the ambition necessary to sustain our democracy?

BEaM. Basement of Hanes Art Center. Follow the signs, down the stairs, around the corner. Just keeping walking until you smell the sawdust.