There are two ways you can react to a “Hey – that was my idea” situation. The first would be to throw a pity party and lament about how unfair life is – if only the car hadn’t broken down and I didn’t have grass to mow and laundry to do I could have filed a patent and been a millionaire by now. The other is to recognize that you were never going to do anything of the sort under any conditions anyhow and simply take the experience as confirmation bias of how brilliant you are.

When I came across Pulitzer Prize-winning author Douglas Hofstadter’s latest work, “Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking”, I chose the latter course. His core theme is that analogies lie at the heart of how we develop concepts, how we construct language, how we understand the world, how we think – something I not only heartily agree with, but a concept I considered myself decades before Hofstadter’s book.

When I came across Pulitzer Prize-winning author Douglas Hofstadter’s latest work, “Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking”, I chose the latter course. His core theme is that analogies lie at the heart of how we develop concepts, how we construct language, how we understand the world, how we think – something I not only heartily agree with, but a concept I considered myself decades before Hofstadter’s book.

Among other things, I fancy myself an amateur student of language. You see, as a parent, by necessity you become an amateur student of a whole host of subjects that previously may have never interested you. For example, I find that parents are three times more likely than non-parents to know that Michael Crichton got it wrong: T-Rex is from the Cretaceous, not the Jurassic, and I have the short video, “Cretaceous Park”, to prove it, created by my then five year-old son, who produced it in order to set the record straight among his kindergarten classmates.

Likewise, as a parent you also quickly become an expert in the field of linguistics as you watch in amazement the literal explosion of language once your children have mastered a basic vocabulary. They start with what they have in their linguistic toolkit and build on it, making telltale mistakes along the way that shows how their mind is working, such as undressing a banana, or cooking water, or breaking their book, before they’ve learned the verbs peel, boil and tear.

Metaphors come next and get incorporated into the very meanings of words: tables have legs, bellies have buttons, and airplanes get tails. The analogies get more complex over time, as we encounter windows of opportunity, haunting melodies and watertight reasoning. These later develop into idioms where sometimes the analogy is still clear, as in ‘bend over backwards’, ‘between a rock and a hard place’ or ‘stacked the deck’, and others where the root is barely discernable, such as ‘kick the bucket’, ‘egg someone on’ or to ‘give someone short shrift’.

One thing I instinctively knew about myself at a young age was that my preferred learning style was by analogy and via storytelling. Rather than feverishly trying to scribe every single detail into my notes as the teacher or professor spoke, I saved those for later (an especially useful approach in today's Google-age) and focused on relating the main and secondary concepts with each other and with what I already knew, working them into my existing knowledge framework and creating a new, expanded or more complex story about the subject for myself. I was mind mapping, or concept mapping as I thought of it, way before it became a thing.

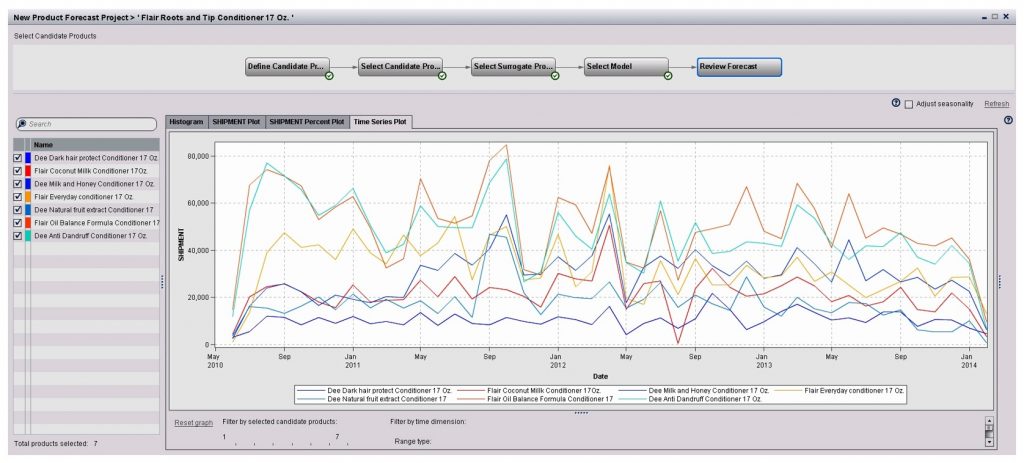

This concept of analogies is what lies behind SAS’ New Product Forecasting solution. New product forecasting (NPF) can be a recurring challenge for consumer goods and other manufacturers and retailers. The lack of product history or an uncertain product life cycle can dampen the hopes of getting an accurate statistically-based forecast. Here are some of NPF situations you might encounter:

- Entirely new types of products.

- New markets for existing products (such as expanding a regional brand nationally or globally).

- Refinements of existing products (such as new and improved versions or packaging changes).

SAS’ patent-pending structured judgment methodology helps you automate the evaluation and selection of candidate analogous products, facilitates the review and clustering of previous new product introductions, and generates statistical forecasts. This structured judgment approach uses product attributes from prior and new products, along with historical sales, to create analogies.

The use of analogies is a common NPF practice. You can see it, for example, in the real estate market, where an agent will prepare a list of “comps” – similar houses in the area that are on the market or have recently sold – and use this to suggest a selling price.

The structured analogy approach requires two types of data – product attributes (for prior and new products) and historical sales (for prior products). Product attributes can include:

- Product type (toy, music, clothing, shirts, etc.).

- Season of introduction (summer item, winter item, etc.).

- Financial (target price, competitor price, etc.).

- Target market demographic (gender, age, income, postal code etc.).

- Physical characteristics (style, color, size, etc.).

The statistical forecast is then built using a structured process based on defining and selecting candidate surrogate products and models. Furthermore, you can combine this with data visualization to study previous new product introductions to gain a better sense of the associated risks and uncertainties.

Using analogies to improve your forecasting should not seem at all foreign – you’ve been using analogies since you were a toddler to expand your knowledge base by connecting and building on what you already know. To find out more, check out this white paper, “Combining Analytics and Structured Judgment: A Step-By-Step Guide for New Product Forecasting”, and learn the details of getting from A to B, of getting from the product history you know to the new product forecast you don’t. You might call it mind-mapping for your new product forecast; See - analogies are everywhere!