What is this math good for, anyway?

–Every student, everywhere

I am a professional applied mathematician, yet many of the mathematical and statistical techniques that I use every day are not from advanced university courses but are based on simple ideas taught in high school or even in grade school. I've written many blog posts in which the solution to an interesting problem requires little more than high-school math. Even when the solution requires advanced techniques, high-school math often provides the basis for solving the problem.

In celebration of the upcoming school year, here are 12 articles that show connections between advanced topics and mathematical ideas that are introduced in high-school or earlier. If you have a school-age child, read some of the articles to prepare yourself for the inevitable mid-year whine, "But, Mom/Dad, when will I ever use this stuff?!"

Grade-school math

Obviously, most adults use basic arithmetic, fractions, decimals, and percents, but here are some less obvious uses of grade-school math:

- Bias and variance: Any child who has tried to throw a ball at a target quickly builds an innate model of bias and variance. In baseball, hockey, and darts, you need to aim for the middle of the target and practice minimizing the side-to-side and up-and-down variation of your shot. My 11-year-old son learned this lesson when shooting a target with a Nerf blaster.

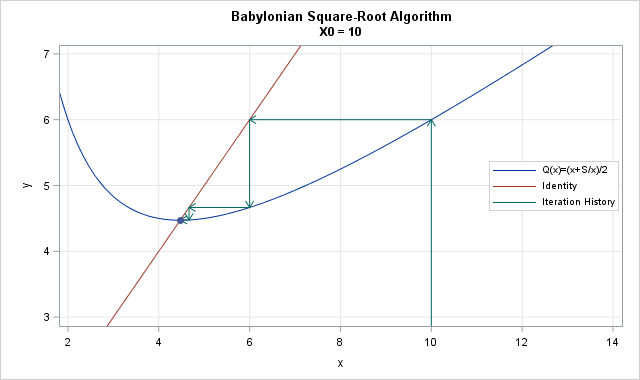

- Iterative methods: In the sixth grade, I learned how to compute a square root by hand. The technique requires applying an iterative algorithm. Iterative methods are the heart of advanced computational mathematics and statistics.

- Newton's method: I like to joke that "all I really need to know about Newton's method I learned in primary school." The Babylonian square-root algorithm is an example of using an iterative sequence of linear approximations to solve a nonlinear problem. As for most iterative methods, you can reduce the number of iterations by making a good initial guess.

High-school math

Algebra, linear transformations, geometry, and trigonometry are the main topics in high school mathematics. These topics are the bread-and-butter of applied mathematics:

- Linear transformations: Anytime you create a graph on the computer screen, a linear transformation transforms the data from physical units (weight, cost, time) into pixel values. Although modern graphical software performs that linear transformation for you, a situation in which you have to manually apply a linear transformation is when you want to display data in two units (pounds and kilograms, dollars and Euros, etc). You can use a simple linear transformation to align the tick labels on the two axes.

- Intersections: In high school, you learn to compute the intersection between two lines. You can extend the problem to find the intersection of two line segments. I needed that result to solve a problem in probability theory.

- Solve a system of equations: In Algebra II, you learn to solve a system of equations. Solving linear systems is the foundation of linear algebra. Solving nonlinear systems is among the most important skills in applied mathematics.

- Find the roots of a nonlinear equation: Numerically finding the roots of a function is taught in pre-calculus. It is the basis for all "inverse problems" in which you want to find inputs to a function that produce a specified output. In statistics, a common "inverse problem" is finding the quantile of a cumulative probability distribution.

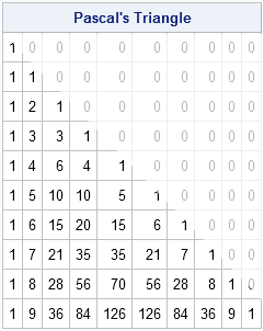

- Binomial coefficients: In algebra, many teachers use the mnemonic FOIL (First, Outer, Inner, Last) to teach students how to compute the quadratic expansion of (a + b)2. Later, students learn the binomial expansion of an arbitrary power, (a + b)n. The coefficients in this expansion are called the binomial coefficients and appear in Pascal's triangle as well as in many discrete probability distributions such as the negative binomial and hypergeometric distributions.

- Pythagorean triples: In trigonometry, a huge number of homework problems involve using right triangles with side lengths that are proportional to (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13). These are two examples of Pythagorean triples: right triangles whose side lengths are all integers. It turns out that you can use linear transformations to generate all primitive triples from the single triple (3, 4, 5). A high school student can understand this process, although the process is most naturally expressed in terms of matrix multiplication, which is not always taught in high school.

High-school statistics

Many high schools offer a unit on probability and statistics, and some students take AP Statistics.

- Extreme value theory: High school students learn the 68%-95%-99.7% rule, which gives the probability that a random observation from a normal distribution is within one, two, or three standard deviation from the mean. That simple rule and elementary probability provide the basis for understanding extreme value theory, which tells you how likely it is to observe an extreme observation in a sample of size N.

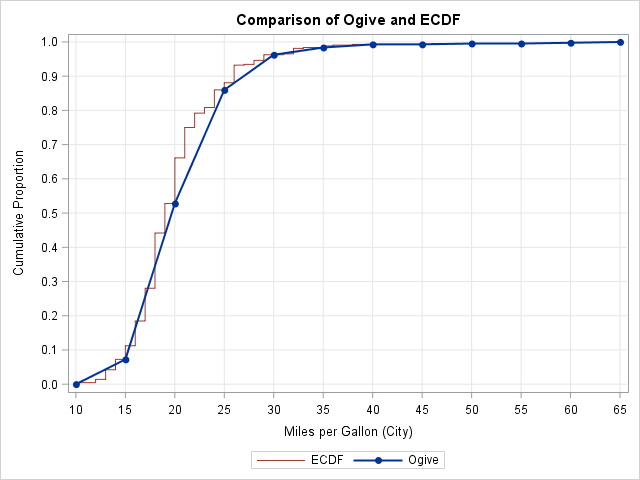

- Cumulative distributions: High school students learn to construct an ogive, which is an approximation to the empirical cumulative distribution (ECDF). Most statistical software does not create an ogive, since it is easy for a computer to create an ECDF. However, it it is straightforward to create an ogive from a histogram.

- Computation instead of tabulation: I claim that calculators killed the standard statistical table. In high school, I looked up probabilities and quantiles in a statistical table (and interpolated between table entries). Today, many students use the TI-84 calculator, which can compute the PDF, CDF, and quantiles of all the important probability distributions. This handheld calculator introduces students to computational methods that are essential for working with probability distributions.

Einstein famously said, "everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler." It is surprising to me how often an advanced technique can be simplified and explained by using elementary math. I don't claim that "everything I needed to know about math I learned in kindergarten," but I often return to elementary techniques when I describe how to solve non-elementary problems.

What about you? What are some elementary math or statistics concepts that you use regularly in your professional life? Are there fundamental topics that you learned in high school that are deeper and more useful than you realized at the time? Leave a comment.

5 Comments

The identity principle (a*1=a and a/a=1) was the basis of converting units, something I did throughout my engineering courses. In freshman chem, I played with some unit conversions and found that one 50-minute lecture was approximately one microcentury.

Yes! Multiplying by one in various guises is a cool trick that I use often. In addition to t is useful for simplifying trig identities and solving integrals. And, of course, it is the basis for adding fractions by finding a common denominator.

By the way, I learned the name "dimensional analysis" for converting units. Chemists call it "stoichiometry." Both sound scarier than "multiplying by one."

Nice post, Rick, as always! Before I retired from SAS, there were a number of times when I had to review high school geometry and trigonometry to do something. It wasn't a daily occurrence, but it happened often enough. Find the formula for a new line segment that intersects an existing segment and passes perpendicularly through the middle of the existing segment was one that popped up a a few years back.

I learned about dimensions of units in school physics. You express the units of all the terms in an equation in fundamental and secondary units (e.g. mass, length, time, temperature) and put these into the equation to work out the fundamental units of the result. It not only tells you what the result should be but is very good at detecting errors in equations. I work in biology but most biologists seem never to have heard of the technique.

Maybe a bit late to reply. About the only math I use is basic set theory which I learned back in 5th grade. First-year algebra was 8th grade, followed by geometry, second-year algebra with series, trigonometry and starting calculus. Along with trig was analytic geometry which took me some time to grasp and was used as the basis for beginning calculus. I dropped calculus senior year HS which was a major mistake in that it was next to impossible to learn in a college setting. There never was a way to know when to integrate by parts, partial fractions, u-substitutions or miscellaneous substitutions. Trig substitutions were sometimes obvious; I recall the professor's scowl when students groaned when trig identities were used as substitutions. "This is mere child's play!"

Except for geometry, virtually no attention was given to mathematical proof. I had no exposure to inferential statistics until my third year at university which is typical of the social sciences.That was also my introduction to SAS of which I was an instant convert after taking FORTRAN as an engineering student.