Academic Research

In an approach akin to FVA analysis, Paul Goodwin and Robert Fildes published a frequently cited study of four supply chain companies and 60,000 actual forecasts.* They found that 75% of the time an analyst adjusted the statistical forecast. They were trying to figure out, like FVA does, whether the judgmental adjustments made the forecast any better.

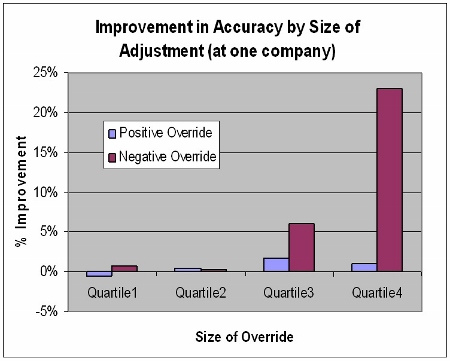

In the chart, they divided the adjustments into quartiles, based on the size of the adjustment. They found that large adjustments (quartiles 3 and 4) tended to improve the forecast, particularly large downward adjustments shown in red. However small adjustments had virtually impact no impact on accuracy – either positive or negative -- which when you think about it makes perfect sense.

In the chart, they divided the adjustments into quartiles, based on the size of the adjustment. They found that large adjustments (quartiles 3 and 4) tended to improve the forecast, particularly large downward adjustments shown in red. However small adjustments had virtually impact no impact on accuracy – either positive or negative -- which when you think about it makes perfect sense.

If you make a small adjustment, even if it is directionally correct, you’ve made at best a small improvement in accuracy. So why bother?

Identifying Waste in the Forecasting Process

We see that Forecast Value Added, Theil’s U, Relative Absolute Error, and the Fildes and Goodwin study, are all going after the same thing – trying to identify waste in the forecasting process.

Activities that demonstrably fail to improve the forecast – or even make it worse – can rightfully be characterized as worst practices.

Research Agenda Under the Defensive Paradigm

Kuhn said that a scientific community’s paradigm guides how they view the world, and legitimatizes the kinds of problems the community works on. Under the Offensive paradigm, the forecasting community worked on ever more complex models and methods to extract every last bit of accuracy from our forecasts. But progress eventually stalled. It seems unlikely that some magical new modeling algorithm is going to deliver us substantially better forecasts.

So the evidence is right in front of our noses – whether we choose to see it or not – that to improve the practice of business forecasting we need to move to a new paradigm. We need a paradigm shift.

Under the Defensive paradigm, the problems and puzzles we work on will be around worst practices. This becomes our new research agenda.

Confessing Your Worst Practices

The reason for all forecasting researchers and practitioners to confess their worst practice sins is so others can learn from them. We need the business forecasting community to be exploring, trying new things, and making new mistakes – not just forever repeating the old ones.

Forecasting is a fundamental business task, yet few companies perform it efficiently and well—or at least not as efficiently and well as they would like. Managers’ attention is often misdirected to the current fads, hype, snake-oil promises – like a 2016 Gartner Supply Chain Magic Quadrant report that made it sound like “big data” was going to solve all our forecasting problems. These distractions, this strict adherence to the Offensive paradigm, can blind us to alternative ways that can truly impact forecasting effectiveness.

*Fildes, R. and Goodwin, P. (2007). Good and Bad Judgment in Forecasting: Lessons from Four Companies. Foresight 8 (Fall 2007), 5-10.

[See all 12 posts in the business forecasting paradigms series.]