In 1993, Trooper Juan Colon was only one year into his 25-year career with the New Jersey State Police when a routine traffic stop for speeding on Interstate 80 ended with him wrestling on the ground for control of the motorist’s gun. A subsequent search of the vehicle revealed 482 rounds of ammunition, a knife and a sawed-off shotgun. He later discovered the man he’d arrested was a hitman on his way to do a hit in the Bronx.

After this type of event, some people would question their career choice.

But for Colon, it was quite the opposite. The event unleashed a lot of questions. Whether he should have chosen law enforcement as his career was not one of them.

The questions running through his head were, “How did this man fit into the criminal network? How was he connected to other crimes, shootings and murders? Was he in a drug ring? What was the drug ring’s area of operation? Were they an actual street gang or just a drug ring? Who were their rivals? Who was their supplier?”

Colon felt if he had enough data, he could use it to connect dots and solve other crimes not thought to be related. And most important – he believed that if he could reduce the time it took to move from collecting data to getting insights and responding, he could even prevent some crimes.

But public health data, he realized, was at least 18 months old. Using old data to make decisions was like driving somewhere using only the rearview mirror to see where you’ve been.

The battle becomes personal

As he was promoted within the State Police, Colon became more driven to solve problems by finding answers in the data.

“When I entered law enforcement, I was unaware of the toll of opioid abuse. But I gained on-the-job knowledge, especially after joining the state epidemiological workgroup. In my role, I gave talks about the dangers of drugs and addiction. In these meetings, I met the mothers, fathers, sons and daughters who had lost a loved one to opioid addiction. That’s when this battle became very personal – as some of those people became friends. I’m still in touch with them today.”

Colon wanted to know as much as possible about every piece of the opioid puzzle

“My goal was to save lives by not just arresting the suppliers and getting drugs off the streets, but by getting drug users into treatment. To do that, I needed to understand the trajectory of drugs through the supply chain – from production to overdose. I had to know what the crime forensic technicians and toxicologists were finding in the drug and post-mortem blood analyses. I needed data. I also needed to understand the disease of addiction and who was being affected the most.”

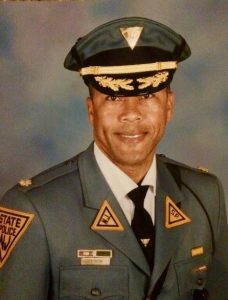

Major Juan Colon was frustrated

It was 2008, and in his intelligence operations role with the New Jersey fusion center, Colon and his colleagues were actively collecting gun violence, burglary and gang activity data statewide. Some of the gun violence involved gang members, and investigators were attempting to connect shooting incidents. While more than 1,100 people were shot that year statewide, the number of overdoses was more than five times higher.

Colon regularly reviewed reported drug arrests involving glassine bags stamped with logos or wording that distinguished the drug dealer’s product. He noticed that the “Batman” stamp was involved in several arrests. Sporadic reports of heroin overdoses also came across his desk. One day, a report indicated that glassine bags stamped “Batman” were found at the scene of a heroin overdose.

Colon wanted to know about all heroin arrests statewide. But with 560 police departments making hundreds of drug arrests daily, accessing all those reports was not possible. So he devised a drug data collection process with four of the nine crime forensic labs where 78% of the police departments submitted their drug evidence for forensic analysis.

The data in the drug analysis results created challenges because it was unstructured, unformatted, and had to be manually cleansed and normalized. And Colon only had two interns to help manually clean the data.

Patterns in the data became apparent

Initially, mapping of heroin arrests did not reveal much. But as more data was cleansed and included in the analysis, patterns in the data became apparent. He instinctively felt that if they could overlay drug data as a backdrop for burglaries and shootings, it would reveal important insights. The results of doing this were quite compelling – revealing empirical evidence that heroin was indeed driving drug arrests, shootings, burglaries and overdoses.

The results motivated Colon to write a proposal titled, “Drug Monitoring Initiative (DMI).” The intent was to start collecting drug analysis results data to help investigators and public health entities understand the big picture.

Colon submitted the proposal to his supervisor. But his supervisor said drug data was outside the purview of a fusion center. The answer was no.

“No” was not the final answer

Colon knew how crucial it was to understand the problem as he surmised that there were more people overdosing than being shot statewide. He continued collecting data anyway. And he started sharing the insights he gleaned from the data with officers investigating shootings and burglaries.

Word spread that Colon had a knack for finding lead information in drug data to support investigations. Drug data collection and analysis became an informal process at the fusion center. In 2012, Colon resubmitted the proposal – but the new fusion center director also rejected the proposal.

Months later, the NJ State Commission of Investigations published a report indicating that the state was indeed facing a heroin crisis – and the Attorney General wanted to use drug data and analytics to address the issue. Ironically, the director who had rejected the proposal the second time asked Colon if he could help meet the Attorney General’s needs.

Colon reprinted and submitted the same proposal. At that point, he had collected nearly five years of drug data – which immediately jump-started their work.

Colon’s “informal” drug data collection effort became the foundation for what was to become New Jersey’s Drug Monitoring Initiative. He was eventually given a full staff to support the operation as the initiative became a formal State Police unit.

“This little ripple of curiosity became a tsunami,” Colon says. In 2015, the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy included the Drug Monitoring Initiative in its national strategy against heroin. Today, about 30 states have some form of a Drug Monitoring Initiative.

To combat issues, you need data and analytics

From the start of his career, Colon was always curious about how people, places, events and things were connected. Through experience, he learned why it is so important to have deep insights to make informed decisions. That’s especially the case if you’re making policy decisions or designing programs to resolve complex problems like the opioid epidemic.

At first, he had problems convincing different entities to share their data. But when people started seeing the success of DMI’s efforts, Colon soon had another problem. Too much data. At this point:

- His personnel were spending 80% of their time manually cleaning and managing the data – and only 20% of their time interpreting it.

- Colon had already tripled his staff, and he knew that adding more personnel still wouldn’t be sufficient to manage the volume and velocity of incoming data.

- There was no more room in the building.

Automated workflows and a new proposal

Colon turned to technology to automate the workflows. And then he wrote another proposal. This time, he proposed creating an integrated dashboard to collect many types of data from different sources and automate the data management process to generate maps, charts and graphs. Having a dashboard would free analysts to spend time interpreting and acting on what the data was telling them.

As it turned out, SAS won the proposal to build the Integrated Drug Awareness Dashboard. At the same time, Colon was retiring after 25 years. But he planned to stay in government to keep fighting the battle against opioid addiction and perhaps help develop more data-driven policies. The CDC had created a special position for him as the national public health and public safety liaison.

A government sequester made him question his decision – and, luckily, Dr. Steve Kearney at SAS heard about his change in plans and called to offer Colon a job.

“I liked that SAS was a data and analytics company. Then I went to the website and read about the data for good movement, and I saw that curiosity was one of the company values – and I said to Dr. Kearney, ‘Wow, this sounds like home to me!”

Silver linings

Despite the pandemic’s downside, one silver lining is that it fueled a resurgence of interest in the fight against opioid abuse and addiction – and for good reasons.

Drug overdoses continue to climb. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 92,000 people in the US died from drug overdoses in 2020 – 75% of these deaths involved an opioid. Provisional data from CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics indicate an estimated 107,622 drug overdose deaths in the US during 2021, an increase of nearly 15% from the estimated deaths in 2020.

Drug overdoses continue to climb. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 92,000 people in the US died from drug overdoses in 2020 – 75% of these deaths involved an opioid. Provisional data from CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics indicate an estimated 107,622 drug overdose deaths in the US during 2021, an increase of nearly 15% from the estimated deaths in 2020.

The numbers are alarming – and they reflect why the opioid epidemic was declared a national public health emergency.

The numbers also reflect why Colon is passionate about continuing to wage war on opioids – which have taken the lives of so many mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters. To do it, we need a continued focus on the issues surrounding opioid abuse. We need sufficient funding for this public health crisis. And we need a solid data and analytics strategy to connect dots and solve problems.

The opioid crisis continues to evolve – and through his work at SAS, Colon is doing his part to fight this battle. He is helping agencies around the world to not just look back, but also look forward – by using complete and timely data and analytics to conduct smarter investigations, make better policy decisions, and keep people healthy and safe.

Learn about law enforcement solutions from SAS

1 Comment

What a wonderful and interesting story of curiosity, resilience and perseverance. Mr Colon is truly a data-driven superhero and it's so inspiring that SAS is a key part of this ongoing story.