Historically, tax havens have been a key tool for tax evaders to store and hide unreported and untaxed money. I would agree with most observers that the Panama papers (11.5 million leaked documents that detail financial information for more than 214,488 offshore entities) are just the tip of the tax haven iceberg - a massive iceberg into which the tax haven boat has crashed.

Historically, tax havens have been a key tool for tax evaders to store and hide unreported and untaxed money. I would agree with most observers that the Panama papers (11.5 million leaked documents that detail financial information for more than 214,488 offshore entities) are just the tip of the tax haven iceberg - a massive iceberg into which the tax haven boat has crashed.

The momentum created by the Panama papers has accelerated an effort already well underway to eradicate tax havens (e.g.: Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes). It’s now becoming expensive, very high risk and low return to use tax havens to facilitate tax evasion.

But in data terms, it’s even less than the tip of the iceberg. The volume and variety of external data that tax departments collect will grow exponentially. This data, combined with analysis techniques, will make it extremely difficult for tax evaders to remain undetected. Tax departments have a unique opportunity to deploy these new capabilities in order to make offshore fraud a thing of the past.

The challenges

The high volume and complexity of the external data has made it difficult for authorities to rapidly mobilise their current operations in order to have a systematic approach. Progress has been made by some of the leading tax authorities, but not all these new capabilities will scale as the volume and variety of external data explodes.

This creates a risk that vital information will be lost in the resulting chaos. A key process for effectively using external data is being able to match it with internal data, and is the starting point for the detection, prevention and management of offshore fraud.

This process comes with a couple of challenges:

Manual processes: Very often, the matching exercise requires some level of manual validation. While this might be an acceptable practice today, it most definitely will not scale.

Limited resources: Government human resources dedicated to prevent, detect, investigate and prosecute fraud and abuse cases are subject to attrition, turnover and are very limited compared with the scope of the assigned task.

Complexity: The nature of the fraud requires a system to be able to identify the linkages between the chains of business involved in the fraud. Detecting fraudulent networks requires the analysis of millions of taxpayers, bank transactions, and company information.

Variety of data: The growing number of data sources will make it increasingly difficult for tax evaders to remain undetected in the countries where the tax departments deploy the processes and capabilities to use this data to detect fraud. Many different external sources complement their internal data, including:

- Leaked data (e.g.: Lux Leaks, Panama papers, Offshore leaks): These sources are valuable as they reveal the ultimate owners and beneficiaries of offshore constructions and provide key information for investigations. However, these sources are never sufficient by themselves for tax fraud enforcement.

- Automatic exchange of information/CRS: These two specific data sources and their implications for tax departments have been described in detail in the blog post The Common Reporting Standard: An opportunity and a challenge for tax authorities.

- Banking transactions: Transmitted to the FIU by financial institutions when there is a suspicion of tax fraud or money laundering.

- Banking transactions to offshore: In an increasing number of countries, financial authorities have an obligation to declare transactions made with tax havens.

- Payment data: This data is transmitted by payment organisations to the tax departments. They can, for example, be useful to detect payment cards linked to offshore accounts.

We believe that by 2018 only 30% of the tax agencies will have the capabilities to systematically use external data in their fraud detection efforts.

Capabilities

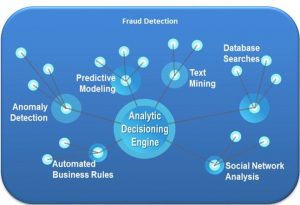

Against this background of challenges, there is nonetheless quite a variety of different, but interrelated techniques available to detect offshore fraud using both internal and external data:

Social network analysis: The starting point of the analysis, this technique matches and integrates data from various sources and discovers networks that will later be used to detect tax fraud patterns. As data is ingested, the system automatically builds networks of relationships among the data (e.g. which directors have directorships at other companies; what transactions link different businesses together, etc.) where shared details are available, such as addresses or telephone numbers (fuzzy matching methods can link similar addresses together).

Automated business rules: The most skilled investigators within the tax authority will have a range of techniques they can employ to uncover tax fraud. By having an environment in which these can be encoded as business rules that are then automated to run across the entire data set, it is possible to leverage these precious resources and their expertise.

Anomaly detection: The system can be used to identify businesses that are not behaving in the same way as other businesses within their peer group. For example, this may relate to the types or volume of transactions in comparison to the declared revenue. Such anomalies are risk factors and useful ways of discovering new types of fraud modus operandi.

Predictive modelling: When a number of businesses known to be associated with offshore fraud are identified, these can be used to train models that look at combinations of variables or business rules and then optimise them to best predict that a particular business or network of activity is associated with fraud.

Text mining: Unstructured information may contain key data. For example, open source data (internet, newspapers) can be used to find more information on a suspect beneficiary owner, its activities and previous cases involving them.

Risk vs. return

The risks associated with tax havens have gone up dramatically as public opinion is taking a tough stand on offshore fraud. Initially, offshore constructions were advised and sold by mainstream banks to their wealthy clients. Today, intermediaries who are setting up offshore constructions for their customers are taking significant legal and reputation risks. This is why most banks will no longer facilitate offshore fraud and fraudsters will have to resort to more shaky intermediaries. The cost charged by the intermediaries has also gone up because of the complexity of the constructions and the risk.

Beneficiaries of offshore constructions are also taking a significant risk, since appearing in any document leaks (e.g.: offshore leak, Panama papers) comes with a massive reputational cost. For small fraudsters, this reputational cost will outweigh the initial tax gain of offshore fraud.

The return of offshore fraud is also lower as it has becomes more difficult to use offshore money. The vast majority of countries have anti-money laundering measures in place, preventing fraudsters from repatriating or accessing offshore funds (e.g. using a credit card linked to an offshore account). Finally, many countries are now launching voluntary disclosure programs. These programs are attractive for taxpayers with offshore constructions as they drastically reduce their risk at a reasonable cost.

Conclusions

Tax havens may soon be a thing of the past as tax departments are adopting a more systematic approach to detect, prevent and manage offshore fraud. But we now have a unique opportunity to deploy a wide array of effective techniques and capabilities, and are on track to eradicate this type of fraud.

The major risk we now see is that the wealthier fraudsters will set up even more complex structures (i.e.: potentially combining tax evasion with a minimum of bona fide commercial activity). Tax departments need to be proactive in tackling these new types of fraud. To learn more, read this white paper: Analytics to Fight Tax Fraud.