You know that feeling when all your ducks appear to be in a row, all the numbers add up, all the boxes have been checked, but you’ve still got a sneaking suspicion that something is wrong? I’m not talking just gut feel here, more along the lines of, “The logic is impeccable, so one of the premises must be wrong, but who am I to question any of these accepted, time-worn, management truths?” In small quantities, the exception(s) prove the rule, but when the exceptions start piling up sufficiently to become a recognizable category of their own, you are surely justified in calling the conventional wisdom into question.

That was precisely the feeling I had as I closed out this Value Alley post from early last year, “Agile Strategy”, which focused on Columbia Business School professor Rita Gunther McGrath’s article and interview in Strategy + Business: “It’s time for most companies to give up their quest to attain strategy’s holy grail: sustainable competitive advantage. The era of sustainable competitive advantage is being replaced by an age of flexibility”.

I concluded the post by hedging my bets: “I have not yet rendered judgment on the impending demise of competitive advantage. My current bias is that firms will still have opportunities for competitive advantage through focus and development of core competencies in a particular Value Discipline, and that firms of the future will be successful by becoming agile experts within their chosen discipline.”

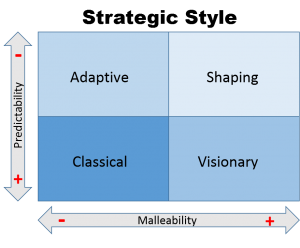

Coming to my attention, my rescue, and easing my angst, was this study from the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) – “Your Strategy needs a Strategy” – well worth the read and critical to my argument below. In it, they expand the concept of strategy from a monolithic, one-size-fits-all approach to suggest that there are at least two dimensions across which strategy setting needs to be evaluated: predictability and malleability. In doing so, they provide a solid framework in which it is possible for both McGrath and her critics to be right, they provide the premises through which the exceptions can be properly understood not as exceptions, but simply as one of several available strategic options.

Pursuant to their two-by-two “Strategic Style” matrix, BCG defines predictability (the y-axis) as, “How far into the future and how accurately can you confidently forecast demand, corporate performance, competitive dynamics and market expectations?”, and malleability (the x-axis) as “To what extent can you or your competitors influence those factors?”

For most of us trained in business school, we are familiar with only one of the resulting four possible combinations, what BCG calls the “Classical” strategic style, based on the default assumption that business is fairly predictable but not malleable – home to such classical business hallmarks as five forces, value disciplines, core competencies and competitive advantage.

With the classical style (+/-) as the default, it’s no wonder that the strategic landscape is so fraught with exceptions, but with the BCG Strategic Style framework in place, it becomes much easier to place these exceptions into their proper category: Adaptive (-/-), Shaping (-/+) or Visionary (+/+).

I won’t comment here any further on the malleability aspect, but leave it up to you to determine if you think it represents a useful distinction. Instead, I want to focus on the factor that interests me the most, and evidently caught BCG’s attention as well: predictability. Here’s what BCG had to say: “Fully three out of four executives understood that they needed to employ different strategic styles in different circumstances. Yet the same percentage were using only the two strategic styles – classic and visionary – suited to predictable environments. That means that only one in four was prepared to adapt to unforeseeable events or to seize an opportunity to shape their industry. Given our analysis of how unpredictable their business environments actually are, this number is far too low”.

That last part is worth repeating: “Given how unpredictable their business environments actually are, …” This inherent unpredictability has been a recurring theme of this blog:

- How variable is my business? My demand? Production? Cash flow? Inventories? Costs? Customer churn?

- How good is my forecasting? While I may not choose to use analytically-based forecasting, don’t I at least want to know how accurate my seat-of-the-pants, business-judgment forecasts are? What are you going to do to manage the random portion of your forecast, especially if you don’t know how big it is?

- Risk, or, Making the “How Certain” decision. Can I quantify my risks? How probable are outlier/Black Swan events? How wide are those confidence intervals? What has been my ability to execute? Are my optimistic and pessimistic plans optimistic and pessimistic enough? How bad can things get?

We are systematically and notoriously biased and overconfident. We are naturally over optimistic in assessing our own plans and equally bad at assessing their risk. We do alright with simple linear interactions, but once the world gets more complex than that, which it is, with its second order (and higher) power-law relationships, we are, as Dan Ariely has said, “Predictably Irrational”.

With this predictability framework in hand, we can readily accept that McGrath’s, ‘The era of sustainable competitive advantage is over’ is directly applicable to the two upper quadrants, the low-predictability Adaptive and Shaping strategies, where agility is not just an asset but a necessity, whereas a focus on leveraging core competencies for sustainable competitive advantage likely still has a place in the Classical and Visionary environments.

Do you need to update your strategy more often than annually? Probably “yes”, but as the BCG study concludes, “you can’t choose the right strategic style unless you accurately judge the predictability of your environment”.