The Current Paradigm for Business Forecasting

So what is the current paradigm that we, the community of business forecasting practitioners and researchers, are operating under? I’d argue that for at least the last 60 years, since 1956 when Robert G. Brown published his short monograph Exponential Smoothing for Predicting Demand, that business forecasting has been dominated by what I’ll call the “Offensive” paradigm.

So what is the current paradigm that we, the community of business forecasting practitioners and researchers, are operating under? I’d argue that for at least the last 60 years, since 1956 when Robert G. Brown published his short monograph Exponential Smoothing for Predicting Demand, that business forecasting has been dominated by what I’ll call the “Offensive” paradigm.

I mean “offensive” in the sense of “playing offense” as in sports, not in the sense of hurting someone’s feeling. Although in the daily practice of business forecasting, feelings are bound to get hurt!

The offensive paradigm is characterized by the development of models and methods and organizational processes that are designed to extract every last fraction of a percent of accuracy in our forecasts.

More is thought to be better – more data, bigger computers, more sophisticated models – and more elaborate collaborative processes that let more people add more (of the grossly mis-named) “management intelligence” to the forecast.

Of course we no longer go to seers on mountaintops for our forecasts. This modern era of Offensive forecasting has taken us a very long way. Particularly in the ability to:

- Automatically diagnose each time series

- Automatically build an appropriate customized forecasting model for each time series

- Automatically generates forecasts.

And do this quickly and on an unimaginable scale.

But in terms of progress toward more accurate forecasts, are we now stuck? Is the Offensive paradigm reaching its limits?

The Paradigm Limits What You See

Your paradigm helps you make sense of observations, and guides the kind of questions you ask and the research you do. But the paradigm can also influence the way you observe phenomena, and in fact may limit what you observe to phenomena that adhere to the paradigm.

There is a large body of literature on how we see what we want or expect to see, and can ignore things that are unexpected or don’t fit the story. Most of you are probably familiar with this famous experiment, but let’s take a look.

Did you correctly count the passes? I did. But about half the people who see this video for the first time fail to see the gorilla. I was one of them.

But even if you noticed or knew to look for the gorilla, did you notice anything else? That the curtain changed color from red to gold, and that one person in a black shirt walked off?

The gorilla experiment is a good illustration that we often don’t notice the unexpected, things we aren’t looking for, or things that fall outside our paradigm. Sometimes we don’t notice because it is things we don’t want to see – because it will rock our world in an unpleasant or inconvenient way. I suspect we all can think of situations where we’ve succumbed to this -- where we’ve failed to see what’s right in front of our nose.

One might expect that trained observers, like scientists, or professionals in some field, couldn’t make the same mistake. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Because of the paradigm they are operating under, their view of the world and how it behaves and their expectations, even trained observers may fail to see the obvious.

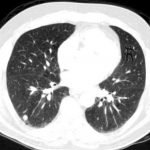

In a 2013 study published in Psychological Science, radiologists were asked to examine scans of patients’ lungs and search for nodules indicative of cancer. How many do you see? (click image to enlarge)

One of the scans – this one – included an image of a gorilla that is obvious when you are looking for it, yet apparently not so obvious when you are looking for something else. Although the gorilla is 48 times the size of the typical nodule, and eye tracking showed most of the radiologists looked right at it, 83% of them failed to notice.

[See all 12 posts in the business forecasting paradigms series.]