Part 2 in the multimodal transformers: AI foundation models series

In the previous post, we explored how transformer-based models became the foundation for the modern wave of multimodal AI. This post continues that conversation but shifts the focus from architecture to application. To be more specific, how organizations extract structured information from unstructured text by using named entity recognition (NER) and related text analytics tasks.

Recently, enterprises have had to rely on one of two very different approaches. One, classic NLP systems built on rules and statistical models. Or two, large language models (LLMs) that can generalize across domains with little to no training. Although both approaches are valuable, they represent opposite ends of a spectrum. Traditional NLP is fast, deterministic, and easy to audit, but rigid and difficult to maintain. LLMs, on the other hand, are astonishingly flexible but computationally expensive, unpredictable, and challenging to operationalize in regulated environments.

Now, a new class of lightweight transformer models—known as small language models (SLMs)—is emerging as a promising middle ground. In this post, we explore how an exciting family of SLM models, the Generalized and Lightweight Model for Named Entity Recognition (GLiNER), combines the strengths of traditional NLP and LLM-based approaches.

Traditional NLP versus LLMs: Two ends of the spectrum

Before the rise of LLMs, developers built most NER systems by using regular expressions, dictionaries, and heuristic rules. These approaches remain incredibly useful. They run efficiently on CPUs, scale to millions of documents, and produce fully deterministic outputs. For tasks where auditability matters—such as identifying sensitive information in clinical records or regulatory filings—these methods still shine. They provide the literal match text, exact character offsets, and clear justification for why a match occurred. They are also easy to deploy in locked-down, privacy-conscious environments because they require no external APIs or specialized hardware.

But their reliability comes at the cost of flexibility. Traditional NLP is only as good as the rules or dictionaries behind it. Even small variations in wording or formatting can break those rules. Maintaining these systems often becomes a never-ending cycle of patching and re-patching, especially in domains where terminology shifts frequently. By tying to predefined labels, traditional methods make it difficult to identify new concepts without significant re-engineering.

The rise of LLMs promised a cure for these pain points. Models like GPT and Gemini can recognize new entities or categories on the fly, even when those categories were never part of their original training. A simple instruction—“extract all construction activities” or “find all mentions of medications” is often enough to get meaningful results without writing a single rule. The flexibility and generalization ability of these models have made them extremely appealing for information extraction tasks.

However, they introduce a different set of challenges. Running a large transformer model locally is slow and resource-intensive, often requiring expensive GPU hardware. Cloud-based inference is faster but raises cost, latency, and data privacy concerns. Most importantly, LLMs are non-deterministic: the same input might produce different outputs at times, making auditing and validation harder. They can also hallucinate—confidently generating entities or facts that do not appear in the source text. These factors limit their usefulness in workflows requiring strict reproducibility and trust.

Given these trade-offs, many organizations are left wondering whether there is a practical middle path between rule-based systems and full-scale LLMs. This is where SLMs, and GLiNER specifically, enter the picture. Table 1 compares the strengths and weaknesses of different NER approaches.

GLiNER: A practical middle ground for modern NER

The GLiNER family was designed precisely to bridge the gap between traditional NLP and LLM-based extraction. GLiNER models are transformer-based, but much smaller than the generative models dominating the headlines. What makes them compelling is that they inherit many of LLMs' capabilities while avoiding many of their drawbacks by virtue of being discriminative rather than generative AI models.

GLiNER models run efficiently on CPUs, making them easy to deploy on laptops, servers, or edge devices without any specialized hardware (though they can still benefit from GPU acceleration). Because they operate deterministically, they produce stable, repeatable outputs. Unlike many LLM-based systems, GLiNER returns literal match text, character offsets, and confidence scores. This makes it highly auditable and suitable for regulated domains. And because they can be executed locally, they preserve privacy and avoid the cost and latency of cloud inference.

Despite their small size, GLiNER models support impressive zero-shot entity recognition capability. This means they can dynamically identify new entity categories from user-provided descriptions. This gives them a degree of flexibility that traditional NLP systems simply cannot match. At the same time, GLiNER avoids many of the pitfalls of LLMs: there is no risk of hallucination, it does not require heavy hardware infrastructure, and it behaves predictably across repeated runs.

The primary trade-off is that GLiNER still benefits from being tuned to the specific domain or task at hand. While zero-shot extraction works well for many general categories, domain-heavy environments such as transportation, finance, or clinical workflows typically see a quality boost when the model is calibrated with example documents or lightly fine-tuned. But this level of tuning is dramatically simpler than maintaining a full rules-based pipeline or training a large generative model from scratch.

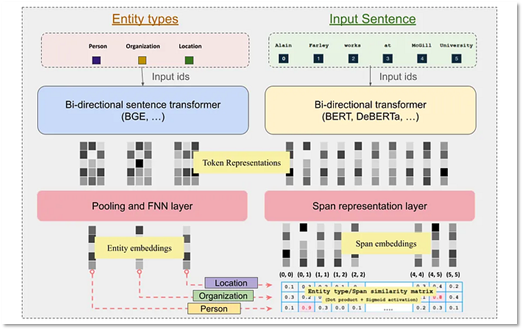

How GLiNER works: A high-level view

At a conceptual level, GLiNER works by transforming both the input text and the user-provided labels into vector representations. Instead of relying on fixed, predefined labels, GLiNER dynamically compares the input against these label embeddings. If a span of text is semantically like the embedding of a requested label, say, “disease,” “equipment failure,” or “construction activity”, it identifies that span as an entity. The model outputs the matched text, its character offsets, and a confidence score indicating how well the span corresponds to the label.

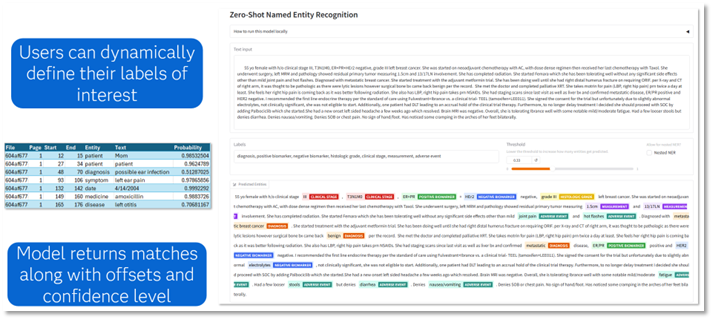

For example, given the sentence: “The patient was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes and prescribed 500mg metformin.” You could instruct GLiNER to extract concepts like “disease,” “medication,” or “dosage” without having pre-trained the model on these terms. GLiNER will identify Type 2 diabetes as a disease, metformin as a medication, and 500mg as a dosage, complete with offsets and confidence levels. This ability to generalize using dynamic labels makes GLiNER extremely powerful for workflows where new categories often emerge, or there are many permutations of a desired concept definition. Figure 1 shows a dashboard view of the output using a different, more complex example.

The same underlying mechanism enables GLiNER to perform lightweight document classification. Instead of looking for text spans, the model simply compares the overall document embedding to a set of category embeddings. It then returns the closest matches. The result is a fast, flexible classification engine that requires minimal setup.

This approach aligns with an important trend highlighted in NVIDIA’s recent paper, “Small Language Models Are the Future of Agentic AI.” The industry is recognizing that although large models provide broad capability, small models provide practical usability. They are faster, cheaper, and easier to deploy in environments where reliability, privacy, and control matter (for example, enterprise applications). For reference, the GLiNER architecture described within Figure 2 is sourced from here.

Where the industry is heading: LLM-Orchestrated SLMs and the rise of agentic AI

The past two years have shown that although LLMs excel at broad reasoning tasks, they are not always the best tool for executing specialized or repetitive functions such as NER, classification, retrieval, or data validation. As a result, a new architectural pattern has begun to dominate research and emerging commercial systems. That is, using large, highly capable LLMs as orchestrators and planners, while delegating most task execution to specialized SLMs.

Instead of relying on a single monolithic model to do everything (which is often needlessly expensive, computationally slow, and overkill for simpler tasks), the industry is moving toward distributed, tool-driven AI ecosystems in which:

- The LLM acts as the “brain”, handling reasoning, decomposition of tasks, decision-making, and task orchestration.

- SLMs and other specialized models act as “tools”, performing concrete actions such as extraction, classification, vision segmentation, retrieval, or structured data generation.

The paper “Small Language Models Are the Future of Agentic AI” underscores this trend. The authors argue that the most effective AI systems of the future will rely on large models not as all-purpose engines, but as generalist controllers that coordinate fleets of smaller, optimized components. This shift dramatically improves efficiency, reliability, and cost.

For information extraction specifically, this trend means that an LLM might eventually be responsible for interpreting the user’s intent. For example, “extract all construction activity mentions from these reports”. It could also include deciding which tools to call and assembling the final structured output. But the actual extraction, the token-level work of identifying entities and capturing offsets, is performed by deterministic, efficient models like GLiNER.

This architecture combines the reasoning power of LLMs with the stability and speed of SLMs. This means producing outputs that are far more robust and cost-effective than using a single model alone. It also reflects a broader convergence between symbolic AI (systems that value determinism and structure) and neural AI (systems that value generalization and flexibility). The next generation of enterprise AI systems will increasingly be hybrid, agentic, and tool-aware.

Where the SAS Applied AI and Modeling Division is heading next

As agentic AI and SLMs continue to mature, they are rapidly becoming the most practical option for enterprise-grade information extraction. They combine the stability and auditability of traditional NLP with the flexibility and intelligence of transformer-based systems. All this without incurring the operational challenges of full-scale LLMs.

Recognizing this, the SAS Applied AI and Modeling division is actively working to incorporate GLiNER-based capabilities directly into our SAS Document Analysis offering. This will enable customers to perform zero-shot and domain-specific entity extraction locally, with deterministic behavior, full auditability, and minimal hardware requirements. It represents a significant step forward in making advanced information extraction more accessible, reliable, and affordable across industries.

In the next post in this series, we’ll shift from text to vision and explore the Segment Anything Model (SAM). This is another zero-shot foundation model reshaping how organizations approach image segmentation in computer vision.

Stay tuned—there’s a lot more to come!

READ MORE | GLiNER multi-task: Generalist Lightweight Model for Various Information Extraction Tasks