Original thinker, effective teacher, advocate for underdogs: These are just a few of the ways SAS Innovate featured speaker Adam Grant has been described.

Add to that corporate culture expert and #1 New York Times bestselling author – most recently for Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things.

SAS CMO Jenn Chase, who introduced him to the SAS Innovate stage in Vegas on April 18, would add one more to the list: mentor.

“I have personally put into practice his research to address imposter syndrome, to build a trusted group of truth-tellers, and how to give and request effective feedback,” she said.

So, she was just as eager as the full-house audience to hear his latest thoughts on ways we can be better versions of ourselves, at work and at home.

Grant certainly didn’t disappoint.

Hidden potential and a full-circle moment

As he made his way on stage, Grant reiterated that as an organizational psychologist his mission is to try to use data and analytics to make people and organizations better.

Ironically, about two decades ago the first business case he ever taught was on SAS. “This is a full circle moment for me,” he said. In looking at all the organizations he has studied through the decades, Grant said there have been multiple opportunities to learn and reflect. “I saw a lot of leaders who missed the hidden potential in their own organizations, and I wanted to get them to figure out how to change faster and achieve more.”

Unlocking the hidden potential within your organization quickly became his theme for the evening.

He began by confessing his own short-sighted vision when one of his Wharton students used a personal experience to pitch the idea behind what is now the online eyeglass provider Warby Parker. At the time, Grant dismissed it, telling the student it would never work, was a terrible idea, even calling it stupid.

Today, Warby Parker is worth over $1B.

“I think of hidden potential as the capacity for growth that is not visible to you or others yet,” Grant said. “It could be the capacity for growth in a person or an idea.”

Change your network, change your mind

The beginning of unlocking your hidden potential, Grant said, is in changing your network. He calls this new network your challenge network and defines it as a group of thoughtful critics who allow you to see your blind spots more clearly and question your assumptions and thinking.

Grant believes building that network comes down to an age-old question of whether you’re dealing with givers or takers. Givers, according to Grant, are constantly wondering, “What could I do for you?” Takers on the other hand wonder, “What can you do for me?”

But it’s not as easy as it might seem to toss people into one bucket or another. There’s a trait that throws us off, Grant said. It’s agreeableness. In his research, he found almost zero correlation between agreeable and disagreeable people and how far you lean between giving and taking at work.

Empower the canaries in the coal mines

“The most valuable people in your network are consistently the disagreeable givers,” he said. To illustrate his point, he claimed these people are the Roy Kents of the Ted Lasso world – rough-speaking but well-meaning. “We need to do a much better job of valuing these people as opposed to writing them off and saying, ‘Eh, must be a selfish taker,’” Grant said. He believes honesty is the highest expression of loyalty, even when expressed in less-than-perfect ways.

He also believes that a lot of leaders don’t even realize they’re silencing the people they need to hear from most by putting heavy expectations on those who share issues to also present possible solutions. “If people can only speak up when they have a solution to a problem, you will never hear the biggest problems, which are too complex for any one person to solve,” Grant said. Encourage people to raise problems, even if they don’t know how to fix them yet. “That empowers canaries in the coal mine who are good at surfacing problems even if they don’t have the authority or the expertise to find the perfect solution.”

Grant is also a proponent of owning constructive criticism. As for employee feedback about your own shortcomings as a manager or coworker, he said, “You can’t hide it from them, so you might as well get credit for having the self-awareness to see them and the humility and integrity to admit it out loud.”

Problem identification, however, is only the beginning of identifying potential in your organization, he said. There are also challenges with something as simple and seemingly-constructive as brainstorming. These include self-doubt in expressing ideas, ego threat and conformity pressure or the “HIPPO” effect – altering the discussion around the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion.

“As soon as that [highest paid]person’s opinion is known, everyone wants to jump on the bandwagon,” he said. “Goodbye, diversity of thought. Hello, group think.”

Grant says you get around this practice with ideas like individual pre-writing/thinking that you bring into a group setting for refinement. He also believes a digital group chat can be one of the best ways to draw out the ideas from everyone at every job level, including those who feel they lack power, status or confidence.

Are you over-confident or over-communicating?

Grant led an audience exercise that had also been conducted at Stanford with the live audience. He asked everyone to clap a well-known song to someone sitting next to them to see if they could figure out the song without words or tune. When he asked those who guessed correctly to stand, there were just a handful of people who rose — something Grant predicted.

“Before someone chooses their song, the one clapping has to estimate the probability that somebody else will recognize that song,” he said. The average person estimates that at 50%. Then they actually clap the song, the correct guessing rate is 2.5%. “Why are they so over-confident? Why are they so sure that one in two people will know their tune when it’s actually one in 40?”

Turns out, in order to clap the tune, you have to hear the song in your head. It’s impossible to do otherwise. It’s also impossible to imagine what your disjointed clapping sounds like to someone who is not hearing that tune in their head.

“I think this is a great metaphor for what happens when you bring an idea to someone else,” he said. “You are not just hearing the tune in your head, you wrote that song. You have spent days, weeks, months, working on that tune and it makes perfect sense in your head. But it’s impossible for someone else to imagine what you’re talking about and you can’t fathom why they don’t get it.”

Repetition is one way around this conundrum, comparing your idea to something your audience is already familiar with. “The art of repetition is underappreciated in leadership,” Grant said. Using his own short-sighted vision of what a Warby Parker could be, he suggested the student could have compared the eyeglasses approach to Zappos and buying shoes online or Netlix and getting entertainment online.

New research he shared indicates that leaders are nine times more likely to under-communicate their vision than to over-communicate it. “If you over-communicate, people get a little bored. If you under-communicate, people think you don’t know what you’re doing and you don’t care.” Grant said he is convinced you haven’t communicated enough until people tell you to ‘shut up, we get it.’ “Then you know you’ve created psychological safety!”

Are you a preacher, prosecutor or politician? (Better to think like a scientist.)

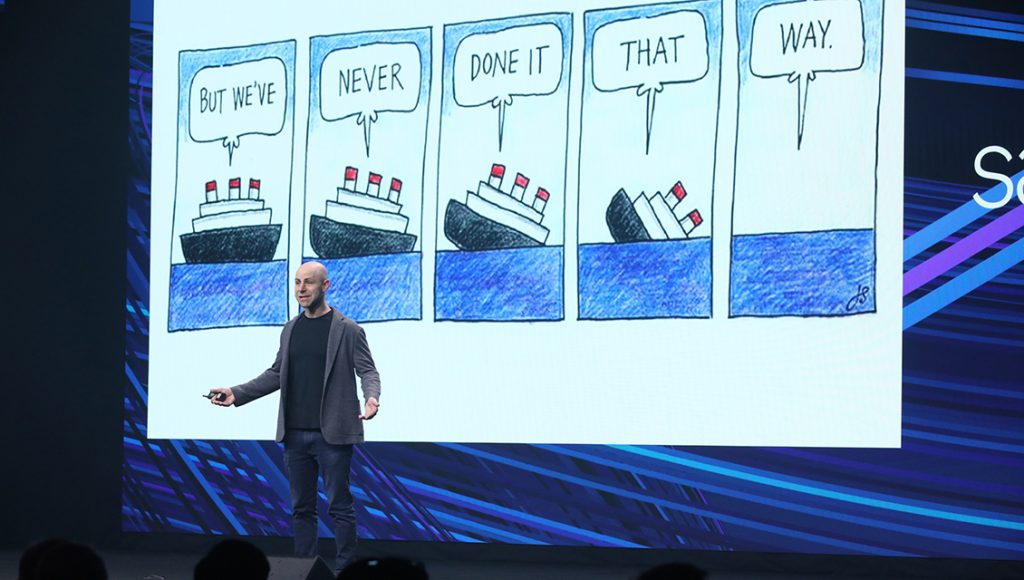

“Too many of us spend too much of our time acting like preachers, prosecutors and politicians,” he said. “When you go into preacher mode, you are basically proselytizing your own views. In prosecutor mode you are attacking somebody else’s views. And in politician mode, you don’t even bother to listen to people unless they already agree with your views.”

Grant encouraged the audience to consider which of these is their biggest vice. His is prosecutor, for which he has earned the nickname The Logic Bully for hammering people with data and facts and hoping that will change minds.

According to Grant, the antidote is to think more like a scientist. “Have the humility to know what you don’t know and the curiosity to seek new knowledge. Don’t let your ideas become part of your identity. Look for as many reasons to look for reasons why you’re wrong as you are to search for reasons that you are right,” he said. “Thinking like a scientist is probably the best way to unlock hidden potential in an organization,” he said.

Chase joined Grant on stage to ask a few final questions, including how to address people in a group setting who question your ideas and evidence. Grant said, “I would say, this is what my experience and data has shown. What data would change your mind?” Keep the dialogue going.