Among the volumes of information about SAS we were showered with during our new SAS employee orientation, two seemingly insignificant tidbits stuck in my mind.

Among the volumes of information about SAS we were showered with during our new SAS employee orientation, two seemingly insignificant tidbits stuck in my mind.

- SAS has dedicated about 12 acres of its campus grounds to a state-of-the-art solar farm.

- SAS prefers employment to outsourcing. Thus, the people we would encounter at SAS, whether in the clinic, fitness center, printing shop, mail room, and daycare center or on the grounds taking care of landscaping, are more likely than not to be SAS employees. SAS employs its SAS consultants and educators.

On first blush, these seemed to be no more than a couple of cute facts to help warm us up to our new home. I couldn’t keep the investment banking corporate adviser in me, however, from reflecting on what little tidbits as such say about the company’s corporate philosophy.

Dedicating some acreage to a solar farm has always been good corporate policy. It never hurts to look like a responsible citizen. And in today’s environment, clean energy makes your image really shine. Preferring employment to outsourcing, on the other hand, is something management consultants and investment bankers would strongly advise against. Outsourcing has been the hottest topic in corporate America over the last couple of decades. And focusing on core competencies is considered the Holy Grail of corporate strategic thinking.

As I dug a little deeper, though, I noticed that SAS walks to a different beat. Investment bankers, for the most part, advise companies that are either public or in the process of being acquired by a private equity firm through a leveraged buyout.

Executives of public companies have a single goal in mind, namely their executive compensation and the management bonus pool. These are usually linked to the company’s share value and stock performance. Private companies in the process of acquisition are managed with a single goal in mind also. The goal this time is the extraction of as much value as possible in the shortest amount of time, to maximize the buyer’s return on investment. Therefore, in both cases, focus is on the immediate maximization of perceived value. This leaves little or no room for long-term planning or strategic thinking.

How does this relate to system fragility?

Let us define fragility as the low, albeit non-zero, probability of catastrophic failure. Due to the low probability of failure, a fragile system may then continue to function, for a very long time, in an apparently normal way. On the other hand, due to the catastrophic nature of the failure, when the signs of such failure start to show, very little can be done to ameliorate the situation. Increasing the reliability (alternatively reducing the fragility) of any system is costly. That cost should be viewed as a form of insurance. Accepting such a cost however is incompatible with short-term thinking.

Is it any wonder then, when we see corporate giants fail so suddenly and so spectacularly? Whether it is the energy wunderkind Enron, telecom star Qwest, mortgage giant Countrywide, Wall street darlings Lehman, Bear and Merrill, Detroit stalwarts GM and Chrysler, household name American Airlines, or the insurance behemoth AIG, they all built extremely fragile ecosystems, through short-term thinking, that ultimately crumbled with a bang. And the short-term thinking is unavoidable as long as you are graded based on short-term performance.

Looking into the SAS solar farm project you quickly realize it was no publicity stunt. The project was built in two stages. The first stage covers five acres and the second, which started generating power a year and a half later, covers 7 additional acres. An environmental gesture would have been satisfied with a single installment.

The farm generates about 3,600 Megawatt hours annually, enough to power more than 325 average US homes. My interest in the solar farm has a fragility tilt. By generating a significant fraction of the power it consumes, SAS has reduced energy fragility in three different ways:

- First it reduced a major source of fragility, namely the delegation of control. This concept was illustrated in my post about cloud computing. Delegation of control degenerates into delegation of ownership as was illustrated in my post about electronic money. By owning a solar farm, SAS has retained control over and ownership of a significant portion of its energy needs.

- Secondly, by pumping that power back into the national power grid, SAS is helping robustize the grid itself by adding an element of risk diversification. This is due to the fact that the power generated by the SAS solar farm is reliable, independent of the power grid itself (see the concept of conditional reliability in my post on cloud computing).

- Thirdly, SAS increases energy reliability via effective network distance reduction, a concept I intend to discuss in some detail in a follow-up post but will briefly introduce below.

Any system can be thought of as a network of interconnected nodes. To go from a node to another you hop along network edges (links). The network distance between nodes A and B is how long (in miles, number of hops, etc.) you need to travel to get from A to B. Since each hop made and each mile traveled require a properly functioning link, the probability of failure of the route increases with its length.

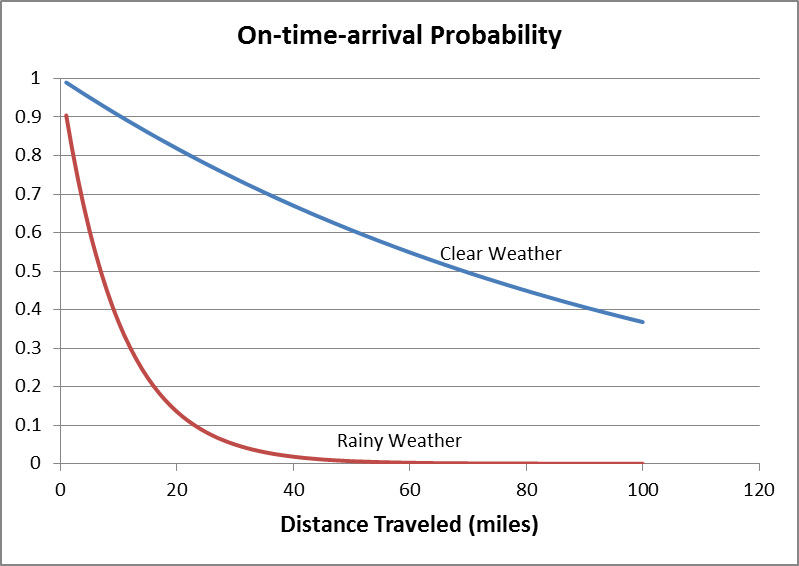

As an illustration, we look at the probability of a sales executive being on-time for a crucial client meeting. We assume that an accident on the major interstate would jeopardize the client meeting. The probability of an accident is 0.01 for each mile traveled in good weather conditions. In rainy conditions, the probability of accidents per mile traveled jumps to 0.1. The graph below displays the reliability of the commute as a function of the distance to the client's location. (Unless he lives within 5 miles from the client, the sales exec is advised to spend the night in a hotel nearby should the forecast call for rain.)

The observation that SAS prefers employment to outsourcing is therefore a statement of a philosophy of ownership and long-term vision. This philosophy which permeates the SAS culture is fundamental not only to the SAS environment but also to its products, software development efforts and client relationship.

Are you then surprised when the presenter at the new employee orientation session tells you that SAS was ranked the ‘Best Company to Work for’ for 2010 and 2011 and among the top three for 2012? Not Me!